Have you ever graded an assessment and wondered or complained how is it possible that after all of your instruction, “How could the students still score poorly and not know the answers?!” I don’t have the solution, but I do know where to place the central piece of this puzzle: Teachers asking the right questions in the first place.

We have to ask deep open-ended questions. Classroom kids — no matter what age — easily give up because they know that within seconds, a strong lead will be received, so why try!

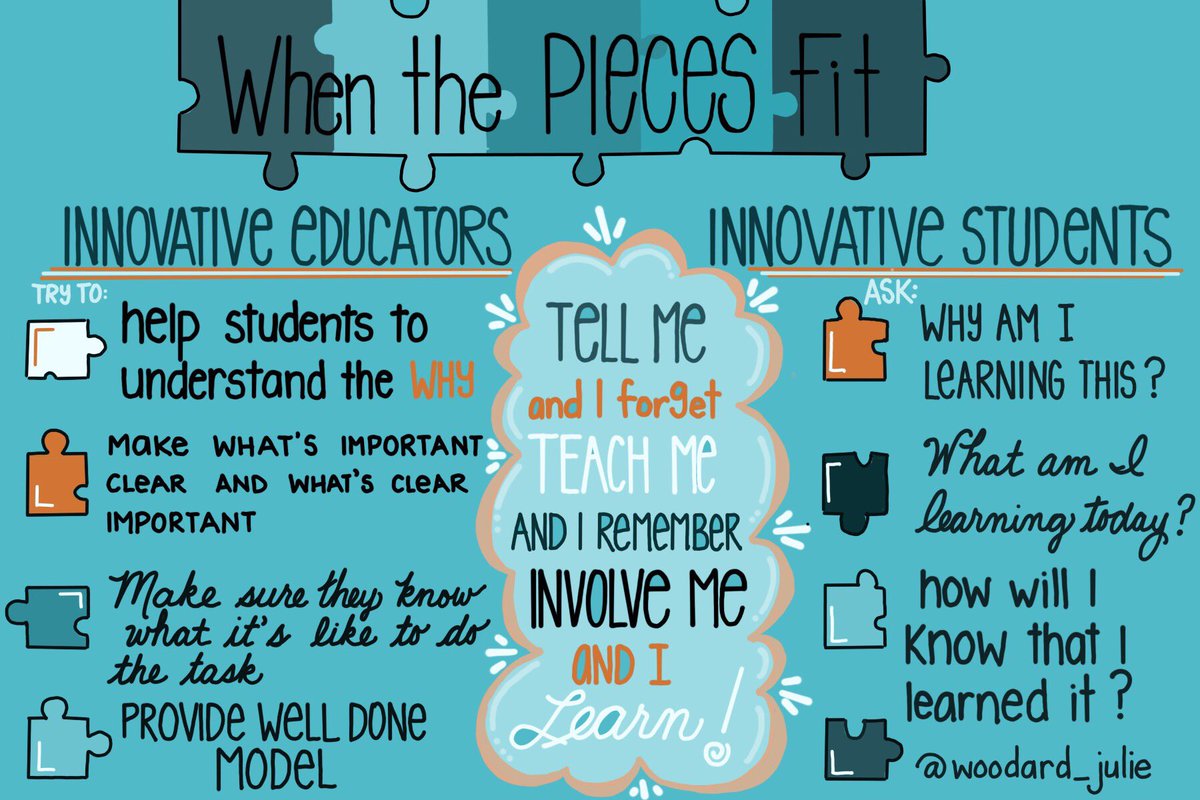

Inquiry is the basis of everything we teachers do. Think about the puzzle of teaching: If we don’t ask, the students don’t reflect and the information — or pieces in this case — is just layed on the desk with no were to go.

When I visit classrooms, whether it is as a teacher coach to give feedback or as a department chair for evaluations and feedback, teachers too often lead students down the trail. Kids aren’t linking related pieces together.

During a recent discussion with my assistant principal about my next coaching cycle, we talked about conferencing, reviewing, and student check-ins. Each of these are coaching rotations on their own and all relate to asking questions. We need to know which puzzle pieces our students know and which they can’t fit together. The only way for us to do that is through questioning. Of course if we lead too much, then kids don’t have to work at finding the right location of that puzzle piece; we do it for them. The students have to be asked the right questions!

We agreed that waiting until next fall wasn’t advantageous for coaching about questioning. Hopefully teachers would begin trying these questions now and have a firmer grip on them when the new school year begins in September.

Therefore, I recently coached our 7th and 8th grade teachers and will do so later this month with the 6th grade math, science, social studies, and English teachers. Thanks to the New Fairfield 8th grade teachers, some additional modifications were made so that the questions are even more relevant for math, science, and social studies. A modified presentation was given to music, world language, art, and health teachers.

The questions in this slide show are meant to move students forward. I hope they’ll help you too. At the request of the teachers, I made mini posters for teachers to hang on their walls to help remind them to ask these deeper questions. Asking Good Questions to Get Great Answers_ Mini posters Asking Good Questions to Get Great Answers

What do you have to lose except increased understanding with students putting more pieces together when you try these questions!

Thanks to two wonderful gurus of conferencing: Carl Anderson and Penny Kittle for their ideas. And also to Lisa Chesser who I found to also be a source of deep questions.